Project Description

NIMBY (Nature in My Backyard) is a continuing series that explores the natural environment found in the backyards, front yards, and side yards of residential buildings of Southern Vancouver Island. 75% of the urban forest exists on what the City of Victoria designates as private property. Trees play a crucial role at the community level. Recent changes in land use, the deterioration of green infrastructure, and increasing temperatures are contributing to a significant public health crisis. The ongoing impacts of environmental colonialism in Southern Vancouver Island have resulted in numerous local extinctions, particularly linked to the decline of Garry oak trees. This series engages with the concept of NIMBY within the framework of urban development, investigating both the nature present in our backyards and the nature that has disappeared due to local species extinction.

Carollyne Yardley. Kwetlal (Garry Oak) Squirrel from the NIMBY series, 2025. 30” diameter Oil on Panel.

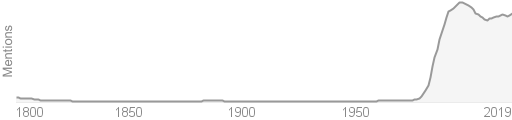

Urbanist groups who are active with local government officials in private and public, also label local opposition to land use changes as NIMBY (Not In My Backyard), a term used in critiques of public engagement with local government regarding local land use. The term first surfaced in a February 1979 newspaper article in Virginia’s Daily Press, “agencies need to be better coordinated and the “nimby” (not in my backyard) syndrome must be eliminated.” The article is quoting Joseph A. Lieberman, a member of the United States Atomic Energy Commission, addressing nearly 500 health scientists in the Fort Macgruder Conference Centre about how to handle the “nimby” (not in my backyard) opposition to radioactive waste disposal.

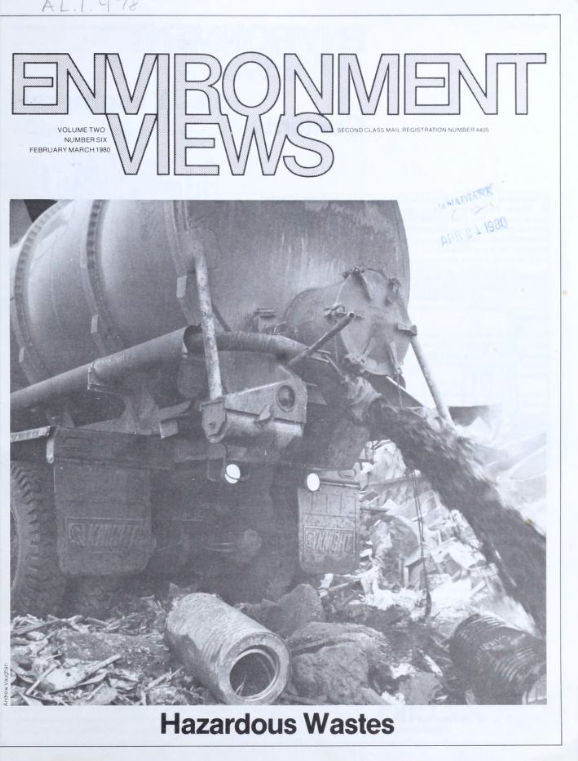

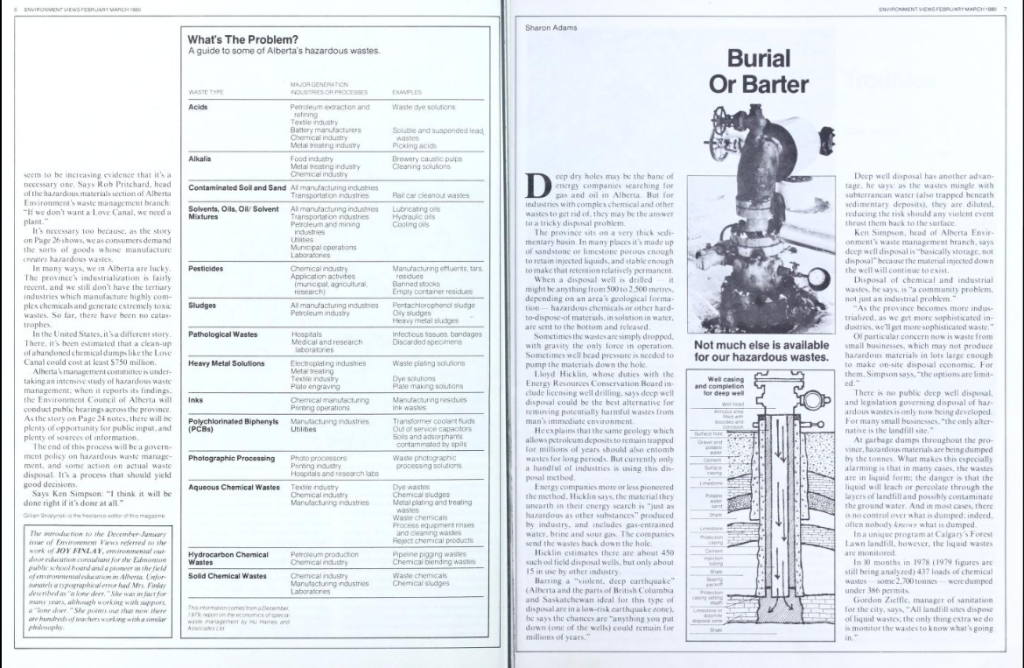

The phrase ‘”not in my back yard”, without the acronym, also appeared in “Hazardous Wastes, an environmental journal discussing the disposal of hazardous waste in Alberta, Canada in February 1980. Over time, the use of the word “nimby” went from being used by the energy, mining, and nuclear industry, which seriously out resources its critics, and was adopted by private market housing advocates in connection to residential land use at the municipal level.

Nature in My Backyard was first proposed in 2011 by David Suzuki to reclaim the term NIMBY, emphasizing genuine community care rather than being coined by the interests of those willing to impose harmful ecological destruction.

Unchanged: Sniatynski, Gillian (February–March 1980). “Hazardous Wastes”. Environment Views. 2 (6): 5. Cover

Unchanged: Sniatynski, Gillian (February–March 1980). “Hazardous Wastes”. Environment Views. 2 (6): 5.

Unchanged: Sniatynski, Gillian (February–March 1980). “Hazardous Wastes”. Environment Views. 2 (6): 5.

The urban forest of southern Vancouver Island is the Garry oak ecosystem.

The Garry oak ecosystem is valued for its cultural history and traditions and for the Kwetlal (camas) food production system that was an important source of nourishment. Many medicines were made from other trees and plants in the ecosystem. Work is underway by Cheryl Bryce[1], a member of the Songhees Nation, and Director of Local Services including Lands Management as a traditional knowledge holder, reinstating harvesting in the meadows for food and medicines, as well as removing invasive plants and educating First Nations and their allies[2]. lək̓ʷəŋən women are the backbone of the Kwetlal food system (Garry oak ecosystems) by managing it for centuries and maintaining their connections to their homelands with traditional laws and practices. The Garry oak ecosystem provides urban Indigenous youth a direct connection to their ancestors and is significant for the continuation and passing of knowledge as traditions change.

In lək̓ʷəŋən, the word for camas and Garry oak ecosystems is the Kwetlal food system. The SENĆOŦEN word for Garry oak used by the W̱SÁNEĆ people is ĆEṈ¸IȽĆ (pronounced chung-ae-th-ch). Garry oak ecosystems arrived after the glacial retreat approximately 8,000 years ago, and at least 1,645 organisms (plants, insects, amphibians, reptiles, birds, and mammals) have co-evolved within this unique ecosystem. Colonial Scottish botanist David Douglas assigned the English name of Garry oak for his friend Nicholas Garry, who was the deputy governor of the Hudson’s Bay Company from 1822–1835.

Prior to European settlement, the majority of the land that now encompasses southeastern Vancouver Island was dominated by Garry oak ecosystems largely from Indigenous agroecological land management over thousands of years which formed the oak savannah. In the absence of these activities, the landscape would be dominated by closed stands of Douglas-fir and Grand fir.

Garry oak and associated ecosystems in this region have a unique local genetic adaptation to the environment and its associated species community would be difficult and costly to re-introduce if lost.

Carollyne Yardley, Western Bluebird: Locally Extinct from the NIMBY series, 2025.

36” diameter

Oil on Panel

The open oak woodlands are home to a diverse bird community, both in summer and winter. Lewis’ Woodpecker, once a resident of the open, dry woodlands of southern Vancouver Island, disappeared early in the 20th century. Concern is growing for the conservation of a number of other birds for which the ecosystem provides habitat, such as Cooper’s Hawk, Western Bluebird, and Band-tailed Pigeon.

The western bluebird is a small member of the thrush family, which also includes the larger American robin.

These bright and energetic songbirds are characterized by their striking blue and rust-colored feathers. Their strong association with Garry oak savannahs and meadows is attributed to several habitat features: nesting cavities in old oak trees, low branches for hunting perches, and open grassy areas abundant in insect prey. As cavity nesters, western bluebirds seek safe nesting sites in tree hollows; however, they lack the ability to excavate their own cavities, relying instead on old woodpecker holes, natural tree hollows, or nest boxes.

Larger dead trees, particularly Garry oaks, are being removed instead of having their limbs trimmed, leaving behind snags for wildlife.

Unfortunately, western bluebird populations have been declining across North America since as early as 1960. Contributing factors include habitat loss, urbanization, predation by domestic cats, and competition for nesting sites. These issues likely led to the local extinction of western bluebirds on Vancouver Island in the 1990s, with the last sightings of non-introduced bluebirds occurring in the mid-1990s within the Mt. Tzouhalem Ecological Reserve. Following their disappearance, bluebirds were absent from Vancouver Island for nearly two decades until the first translocated bluebirds were introduced to the Cowichan Valley, from Washington, in 2012 through an initiative called the Bring Back the Bluebirds project, where individuals can adopt a nest, support the effort, and make donations.

This introduced population successfully laid the first clutch of bluebird eggs on Vancouver Island in over twenty years. Today, if you encounter a western bluebird on the South Island, it is likely one of the birds from the Bring Back the Bluebirds project. @cowichan_valley_bluebirds

Resources

Carollyne Yardley, “Urbanists vs. the Nature in My Backyards. District of Saanich – Special Council Meeting for Draft Quadra McKenzie Plan July 7th, 2025,” Squirrelformayor.com

https://www.squirrelformayor.com/2025/07/urbanists-vs-the-nimbys-district-of-saanich-special-council-meeting-for-draft-quadra-mckenzie-plan-july-7th-2025/

Suzuki, David., 7 June, 2011. Accessed 22 May 2025.

https://www.straight.com/article-396834/vancouver/david-sazuki-embracing-new-kind-nimby-nature-my-backyard#

Notes

[1] Bryce, Cheryl. “Meegan. Online On Land.” Open Space. 2019

https://vimeo.com/405250132. Accessed 6 July 2023.

[2] Acker, Maleea. “Caring for Kwetlal in Meeqan.” Focus Magazine. 2020.

https://www.focusonvictoria.ca/earthrise/caring-for-kwetlal-in-meegan-r20/