My latest project was developed through a variety of current events, socio-cultural,material, embodied knowledge, citizen science and research. Earlier this year, British photographer Henry Jacobs captured images of an Eastern grey squirrel carrying blue and grey plastic material for nest making, showing the impact of human litter on urban animals in the London Borough of Haringey, UK. As a result of this news story, I became curious about the material in local squirrel dreys (nests) and hired a drone pilot from Elite Drone Solutions to capture footage of nests which are typically 30 to 60 ft from the ground. This led me to visually learn more about tree squirrels’ symbiotic relationship with trees and the material connections between human and nonhuman worlds. From the elevated vantage point, I could clearly see the bronchi pattern of tree branches and what appeared to be small pieces of white plastic in the nest. The message gives illustration to the Norse origin story of Ratatoskr, a drill-tooth squirrel who scurries up and down the world tree Yggdrasil carrying messages between the sky and the earth gods. The message was clear – plastic has enveloped our world.

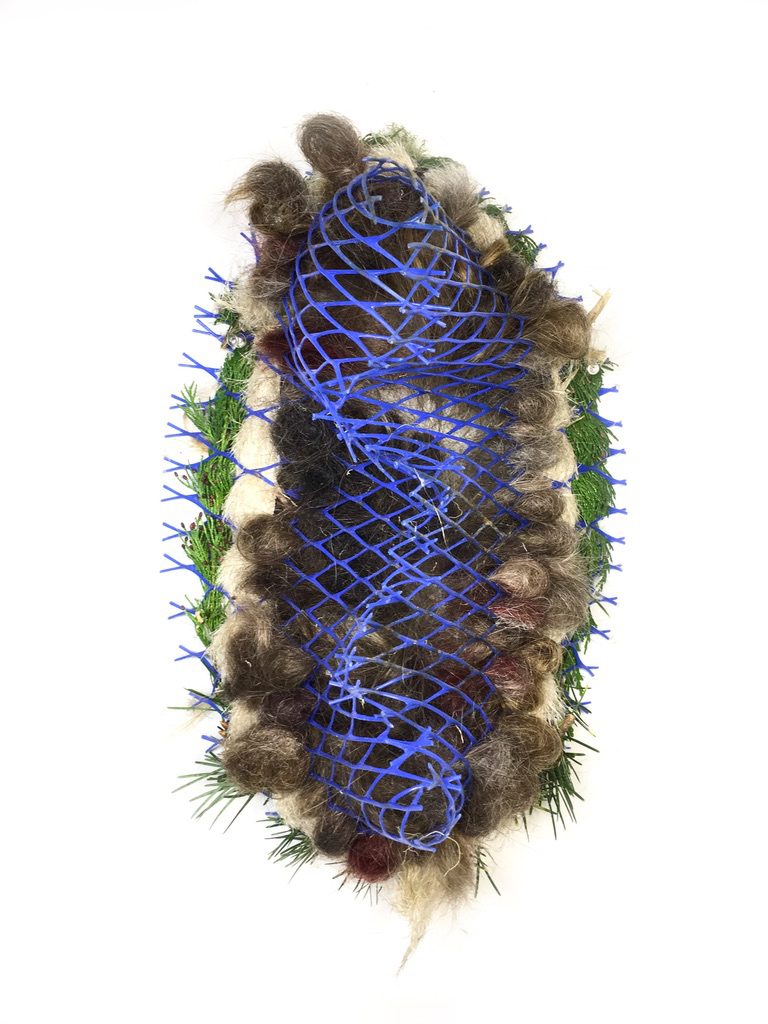

Drone footage also showed the roots of a squirrel drey emerging like the roots of hair from a body. Working with this idea of root systems, I circled back to Deleuze and Guattari’s (1987) Iiguration of the rhizome to ask: Could I create new growths that we don’t recognize uniquely as human or nonhuman in a gallery setting, but still feel caring and kinship to nonetheless? How will the root system of vegetation help me visualize the imbrication of boundaries? A combination of a kitchen sponge, nylons and alfalfa seeds helped to materialize a penetration of living and non-living matter, and I was able to grow alfalfa seeds on human hair. The imbrication of organic and nonorganic boundaries in this experiment helped me to simulate the idea of a ‘symbiogenetic join’ in another artistic way.

I continued to forage and collect natural (seasonal) and non-natural materials looking for material connections. After handling local lichens, I discovered they are found worldwide and provide both food and home to small invertebrates, slugs, snails, migratory birds, butterIlies, and are important winter food for larger animals including deer, caribou, and humans. Lichens are used locally by the native Douglas squirrel and rufous hummingbird for nest construction.

In the gallery space the project creates a topography within the room, with each piece operating on its own, but collectively as a larger landscape. There are components that are growing and decomposing – alfalfa sprouts; and some with the potential to decay – lichens, woods, human hair, and feathers. Plastic, metal and glass elements are non-biodegradable and act as archival remnants of this geological epoch. The colour palette is dictated by the found materials; city workers and property surveyors use pink Ilagging tape to mark boundaries. The materials are evidence of breached and overlapping boundaries with cut, shed, decomposed, unearthed, detached and discarded materials; blue plastic gloves, rusty bedsprings, a blue plastic tree protector, pruned tree branches, cedar boughs, and human hair. The layering of detritus created something new and stronger which helped me examine ideas where the new entity becomes more durable to environmental conditions.

![Squirrealism: Psychometry (IIC) in artistic practice. [Online presentation] International Multispecies Methods Research Symposium, University of Saskatchewan, Saskatoon, Canada.](https://www.carollyne.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/Screen-Shot-2023-06-18-at-9.16.32-PM-copy-1-500x383.jpg)